EL UNDERGROUND 001: CLARISSA BITAR

"Five times a day, you'll hear the call to prayer; I would always enjoy going outside and trying to guess what scale it was in."

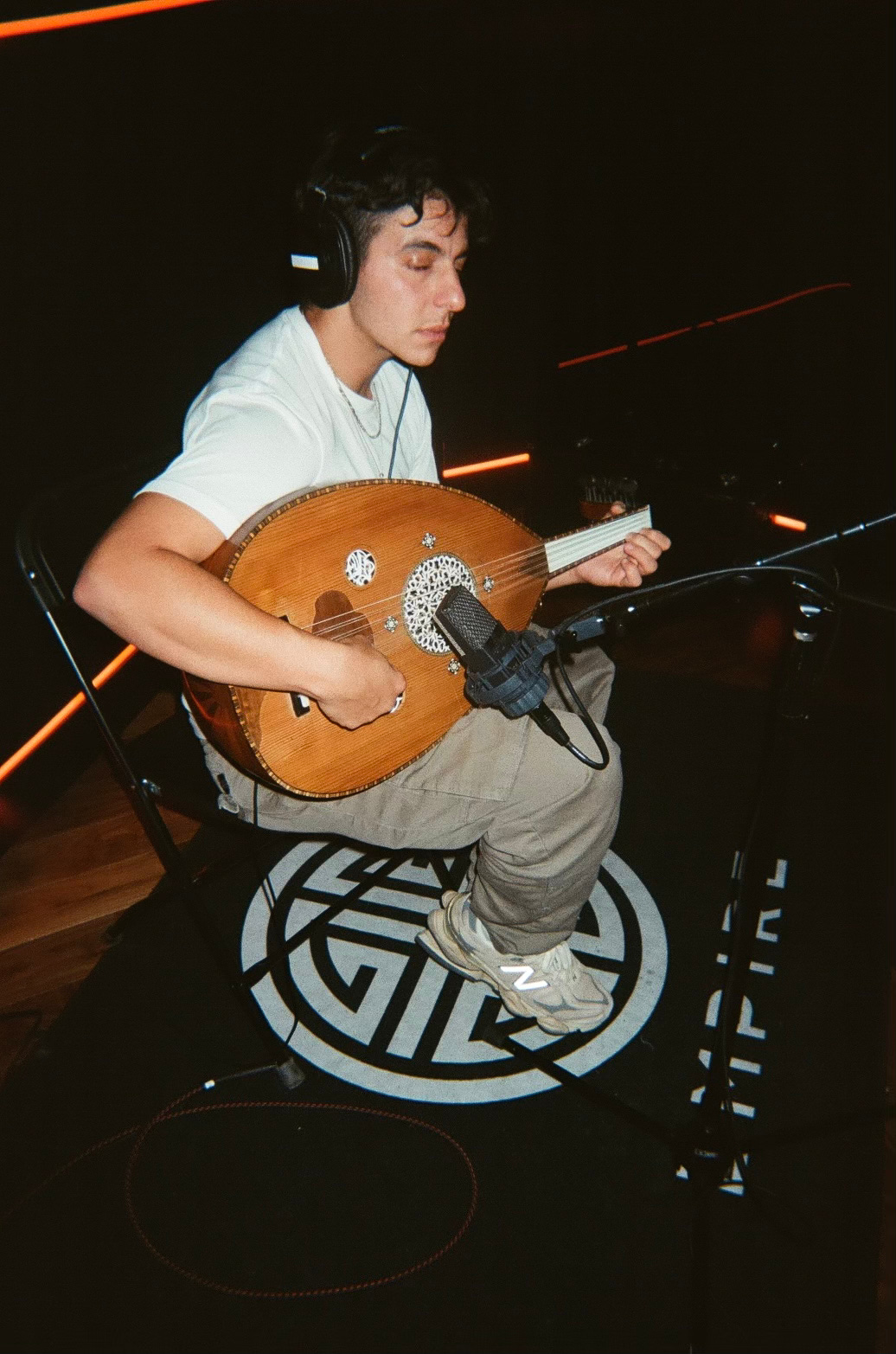

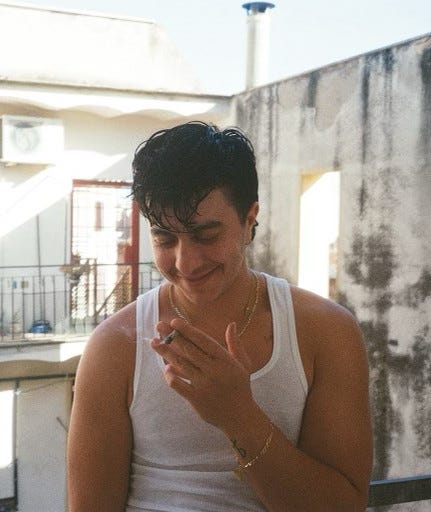

I arrived to Centro around 7pm last Monday to have a second drink with Clarissa Bitar. We had met before 2024 ended at a dimly-lit bar off Parque Mexico, brought together by writer, organizer and Clarissa’s partner Niki Franco. The pair were on their way to Oaxaca, oud in its case atop a small mountain of suitcases. It was now 2025, they had just returned from the coast, and we were separated only by several flights of stairs.

Clarissa’s skill on the oud has gained them global renown. The child of Palestinian immigrants to California, they had been curious about the instrument from a young age. Eventually a professor put one in their hand and kickstarted a journey toward sonic ancestral reconnection. They would go on to release Hassan Sabi (which roughly translates to “tomboy”), a full-length of original oud compositions, after two EPs: debut Bayati, named for a maqam similar to the minor scale in Western music, and collaborative oud-poetry EP Bellydancing on Wounds alongside celebrated Palestinian writer and frequent collaborator Mohammed el-Kurd.

Bridging the gap between folk tradition and experimental composition (like “Freedom”, a collaboration with Lara Aburamadan and Triagonal Disk that blends fast-plucked oud with electronically altered vocals) has made Clarissa a key artist of the Palestinian diaspora. As of late they’ve been exploring other genres, including salsa and reggaeton (“all day since Bad Bunny's album was released, we've been on that,” they tell me later with a chuckle), recently sharing a light-hearted cover of Don Omar’s “Salió El Sol”. Elsewhere in the Latina Belt, Clarissa cites Brazilian baile funk as an influence on the deliciously disjointed percussion running through new single “Leh.”

The track is the first time Clarissa felt comfortable enough since transitioning to record themself singing. They bemoan lost love with a husky, sensual delivery —the opening lyrics, translated from Arabic: “Why did you do this to my heart oh sweet one / Why is your lover neglected?” The intimate camcorder home film opens with a mirror shot of Clarissa’s top surgery scars and features shots of them showering, playing the oud, having their face caressed, and generally being a swaggering beefcake about the house (they’re a Taurus, obviously). From their visuals to their method, Clarissa’s work takes up new space in the oud’s ancient tradition and in a contemporary cultural memory of Palestine.

“When you don't have access to your archives or history, it becomes a revolutionary act to collect all soundbites and piece together memory collectively,” Clarissa tells me. “There's a huge weight when you're in diaspora experiencing a different reality. You have to be real to your conditions and respectful to what people are going through. Finding that balance is a project.”

Ciudad de México is at an altitude that still leaves me out of breath after a year. A few hugs and cheek kisses later, Clarissa and I sit with a bottle of Havana Club between us. We settle into a conversation about Palestine, diaspora, transness, the oud, and what happens when an instrumentalist finally feels at home in their voice.

I’ve been locked into this album the poet Chariot Wish showed me. I thought it was an oud, but it turned out to be the Malian kora. It’s very light, almost like a lute. I've been thinking about how instruments can meet cross-culturally, like how the arpa jarocha from Veracruz relates to the Venezuelan arpa llanera. Where do you place the oud, as far as lineage?

The oud is the ancestral instrument of the lute, and one of the oldest string instruments. A lot of people say it originated in central Mesopotamia, which is modern day Iraq. Europeans came to the Middle East, took it, and it became the lute, transforming based off European music and what was desired at the time. They added frets and it ended up pitching higher. Western music is a polyphonic tradition, which means they're trying to stack chords on top of each other, which is why they wanted to delineate with frets to show where exactly the notes are. The oud is fretless; we don't play chords in traditional Arabic music. We have multiple scales, and the frets inhibit certain notes. The instrument then made its way to Spain and became the guitar, which was brought to so many parts of the world through colonization. I remember when we were in Cuba and they were like “this is a laúd.” It was interesting to see the full circle moment of [the oud] being brought by the Spanish and, through a different cultural mix, becoming a Cuban folk instrument.

Even just the words, oud and laúd…there are so many convergences between Spanish and Arabic. So Arabic music isn’t polyphonic?

It's monophonic. In Western music, you've got major scale, minor scale, maybe two variations of minor. We’ve got tons of scales; I named my first EP [Bayati] after the first one I learned. I was nervous about putting out music, being in diaspora. A lot of the traditional Arab musicians who grew up and performed in the Middle East had a particular skepticism of my ability. It was very important that my first EP respect the tradition and showed people that I was a student of the theory, that I wasn't just the Palestinian who grew up in America grabbing this thing and doing whatever the hell I want.

What drew you to the bayati maqam?

I think it has a lot of minor section in the scale: the upper half of it gives that sad feel, and then the bottom has this half flat, which is a quintessential note in Arabic music that you can't find on the piano or on the guitar. Imagine if you needed a red key in between the black and the white key to get that half flat. It's sometimes jarring to people whose ears have only been trained by Western music, but for people who grew up in Arabic traditions it evokes a lot of emotion. Our music tradition is not one where people are quiet when they like something: if people are vibing, they're calling out and yelling. I've noticed over the years, even just playing for my grandparents, that they would respond when I would modulate and hit that half flat. It's a significant scale, specifically in the Levant, which is very present in dabke.

A lot of religious music is in that scale too, no?

A lot of the formation of scales in Arabic music was because of the recitation of the Quran. Five times a day, you'll hear the call to prayer; when I was in Palestine I enjoyed going outside and trying to guess what scale it would be in. It was a geeking-out moment for a musician, but a beautiful thing to be able to sit and listen to it. A lot of times they're pre-recorded, but before they would have the reciters trained in the maqam.

That's so beautiful. Were you going back often growing up?

The first time I went back was when I was 17. I was always told like, “when it gets better;” at some point, you have to commit and just go. From that point on, I fell in love and wanted to continue going. My family is from Bethlehem and Jerusalem, and I was back right when COVID hit before everything shut down. We made it back, and I haven't been back since. I wanted to go back this past year, but then with the genocide one month turned to two turned to three turned into a year.

That really resonates. I went to Venezuela this past March and then everything exploded again after the election. In diaspora, you’re kind of always trapped in time if you're someone who gives a fuck about your land. It’s like “damn, it's been this long since I was back.” When I landed back in Venezuela last year, it had been 16 years. I grew up and then returned, and it was a moment of realizing that I wasn’t from there, even if I’m of there.

Exactly. The first time I went back, I felt deflated from this realization of being so different because I grew up in diaspora and have a different set of experiences. I'm so far removed from the reality of what my family in Palestine experienced. The second time I went back with my music, it gave me this security in myself that I was respecting my culture and my tradition and participating in the way that I could. I was asked to play a concert in Bethlehem and like 500 people showed up. It was honestly emotional; the organizer got up on stage and gave a speech about how proud he was that kids in diaspora haven't forgotten their Palestinian culture and connection to their homeland. For me to hear that in Palestine at a concert that they threw because they were so excited that I played there was really special.

Between Bayati and Hassan Sabi, how have you grown as a musician?

Bayati was throwing it out there and seeing what would happen. It was surprisingly well-received, and I was happy about that. Hassan Sabi was something else. I was trying to push my queerness in the community where for a long time I would tiptoe around that. I still wanted it to be a very traditional album; I wanted some uncle to hear this and be like, “who the heck is that” and realize it's a young queer person. Bayati was also my interpretations of folk tradition. Hassan Sabi was the first album of all my compositions. I showed that I can play traditional and then I showed my take on that and mixed genres. That was also part of me being diaspora: I've been influenced by so many different genres, and I wanted that reflected.

Before Bayati you released Bellydancing on Wounds, where you play oud alongside Mohammed el-Kurd reciting poetry. He’s also written a lot of lyrics for you. I was wondering about your artistic partnership, and your relationship to lyric and voice.

We met at a National Students for Justice in Palestine conference in like 2017, in Houston. I was so impressed by his poetry. For someone so musically oriented, I have a hesitancy toward lyrics. I think a lot of it has to do with diaspora and feeling like I haven’t had the “proper experiences.” A lot of Mohammed’s poetry in that project is very much about growing up and living in Palestine. I felt my job was to support and elevate that experience. When I needed inspiration, I would put on his poems in the background to give me some emotion to evoke. “Homeland Security” I wrote when he was going through the eviction in Sheikh Jarrah; he had recorded a poem that he didn't want to release, and I played along to it. For “Leh,” I sent Mohammed the track and within a couple minutes he sent back the lyrics. I decided to try to sing it, and honestly…I sounded hot. I sent it to some people I'm close to and they gave me positive feedback, which made me feel confident. Since my transition, I haven’t had a public moment addressing that with the community.

And then the video begins with your top-surgery scars! Any statement aside, I love how the whole thing is shot, how the lyrics are about heartbreak and yearning but the video is the lover’s lens.

I went through a tough breakup the year before: a six-year relationship that was abusive and transphobic. It's tough already to be transitioning, and then to have a partner trying to shut you down is really damaging to your confidence. I like that the lyrics channel that but in the video I'm singing and it’s like I’m smoking a cigarette and being like “you broke my heart, but I don't give a fuck.” Occupying a very traditional space and being queer also made me feel nervous to be out because my crowd is the uncles and people who appreciate traditional music. When I look back at old photos there’s definitely a tension with that performance of the expectation of femininity. It’s a negotiation of how much can I be myself and how much of my queerness I need to swallow. In hindsight a lot of people were like “wow, it's so amazing to see a woman playing oud”, and that’s so important…

And then you’re like “plot twist!”

[Laugh] Often people meet me and it’s this genuine and sweet way of expressing how impressed they are. It’s induced a fear in me: what if that’s the only thing that makes me important right now? All these things start to run in your head, that people won’t support you when they realize you’re a queer person. It’s like… just listen to the fucking music.

What would the next show in Palestine look like for you, hypothetically?

I would like to be able to present my music as an artist and not an instrumentalist covering songs, to work with Palestinian artists and put on a band. I think that's it's something that's very doable, but artists in Palestine can't even make art right now. So many artists that wanted to have shows in Europe or outside can’t because conditions are so bad. It’s a heavy question, because it feels so far from reality right now. If you want to get down to brass tacks, it becomes virtually impossible to put on a concert during genocide. Besides the fact it would feel tone-deaf, it’s a hard thing to navigate in this moment. As much as I'm a Palestinian artist who should be supported, I'm also not being bombed right now. How do you reconcile promoting yourself when you get online and it’s just blown bodies?

In diaspora, your positionally is different. People outside Palestine (or, for me, Venezuela) are all “oh, I’m so sorry” and then you’re forced to speak about something that you’re not actively experiencing.

We have to be really intentional about sharing, and think about what we are actually contributing and what is performative. At first it was like “okay, fuck all of our art right now, we're focusing on this” and then realizing you’re shadowbanned, so how effective are we being if we have tens of thousands of followers but only 300 people are seeing your story? When you're an independent artist and social media is one of the only ways you can promote your work for free, it makes it a really difficult question. Are we supposed to perform misery? You can’t disregard people's pain. I was having a conversation with Niki about how Palestinian artists have been historically blocked from media after the creation of the State of Israel. From a specific period of history, we don't have a lot of recordings; not because they don’t exist, but because artists weren't able to have a presence in history.

Right now there’s a lot of correction of that in a sense, with media like The New York War Crimes and Sonic Liberation Front streaming and publishing independently. Even then, in my research for our conversation, I saw that on Spotify your #2 place with the most listeners is Tel Aviv, and it’s like…

[Those listeners] are not in Israel! When you're on Spotify For Artists, you can see what playlists you'll be added to. So many of the playlists are, like, Israeli Mix.

Please…

I'm like…dude...

It's like the salad.

When you go through such a violent, colonization and dispossession, many Palestinian artists have been put in that position where they will throw that trap of “let's do an event with Israelis and Palestinians making music together and healing” while we're being bombed.

The cover photo of “Homeland Security” is a photo your family took. It runs in your blood, not to fall for attempts like that.

I care about my family's history so much that to be anything but fiercely anti-Zionist…there's nothing in my body that could do that. When you know your ancestors, when you see what your grandparents were literally looking through…that archive has like 300 photos, and some of them are graphic. Thinking about my grandpa and his brother, and the fact that this has been going on for so fucking long that you cannot tell —unless the photos are in black and white— whether it was now or in 1948, is really heavy. There's just no other choice when you respect your people's struggle, and it's a weird thing to negotiate as an artist working within the super extractive, advertising-heavy, capitalistic mentality. You see it playing out with trying to elevate artists to a certain extent. We got a Palestinian show on Netflix, a Palestinian artist playing Coachella, but what is actually changing?

It’s a moment of energy and of listening to Palestinians and of the discourse changing —but is it stopping the fucking bombs?

Exactly. People on a general basis are way more educated than they were, but are the forces running the show listening to what people are feeling? These people have seen a rise in profit. It’s such a violent thing to see colonization happen in real time. I have cousins that live in Jerusalem, from this village right outside that was taken in 1948 —Ein Karem, which is where my mom's side is from. If they go back and visit, they have to knock on a door and ask the Jewish family who is there if they can see the home. They're living five miles from it and still experiencing such a dispossession. So many people in Gaza are not supposed to be in Gaza: they got pushed in there.

There are a lot of roles in the revolution: musicians, educators, healers, militants. I think that's one reason why we have so much intra-Left fighting. Some people think everyone has to have the gun pointed or know the theory. Some of us have to archive and bake bread and care for others and steward the ancestral music.

That's an important perspective. The intra-Left fighting can be so intense, and it honestly weighs on you more than a Zionist being like “fuck you,” because you're like, well, fuck you. As an artist, you require community support. When the community is exhausted, I feel crazy asking for that. You have to be like, “hey, we've been inundated with misery —here's some music.” I have to tell myself as an artist that I’m feeding my community. This is how we continue to keep ourselves strong.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Listen to Clarissa Bitar’s guest mix here.

Mutual Aid and Resources

Evacuated Palestinian Family in Egypt

Since last year, New York-based collective Casa Gaza has been fundraising for the Shaban family from Jabalia in northern Gaza. Help them meet their goal by donating here or (preferably) directly to one of the organizers via Venmo.

Families Displaced by the Eaton Fire in California

These constantly-updated spreadsheets compile a number of Black and Latinx families affected by the fires in Altadena and Pasadena. They also link to various other resources, including a list of displaced disabled folks.

La Red Afro-Cubana de Personas Trans

RACT is sending a Black trans delegation to Cuba at the end of the month to distribute much-needed funds and supplies to the island’s trans community. New York — today at Mad Tropical there will be a party where 100% of the funds go to this cause. If you can’t make it, donate here, or via CashApp ($lexicon91) or Venmo. ***DO NOT MENTION CUBA IN THE DESCRIPTION***

*This list is rotating and non-exhaustive, changed monthly to highlight different causes. I pledge a part of paid earnings to each cause, and do my best to vet them. If you have any concerns, comments, or urgent aid links to send my way, please email (work@erpulgar.com) or DM me.